stunted Norfolk pine

ern_pdx

13 years ago

Related Stories

GARDENING GUIDESGreat Design Plant: Pinus Thunbergii ‘Thunderhead’

Thunderhead pine adds year-round strength and structure to the garden

Full Story

Rooting for Indoor Trees

Houseplants tend to get all the glory indoors, but trees deserve their place in the sun — and in your living room, your entryway, your ...

Full Story

HOUZZ TOURSMy Houzz: Accessibility With Personality in an 1870 Home

Hand-painted murals and personal touches fill an accessible home with warmth and charm

Full Story

FARM YOUR YARDHow to Build a Raised Bed for Your Veggies and Plants

Whether you’re farming your parking strip or beautifying your backyard, a planting box you make yourself can come in mighty handy

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESWhen and How to Plant a Tree, and Why You Should

Trees add beauty while benefiting the environment. Learn the right way to plant one

Full Story

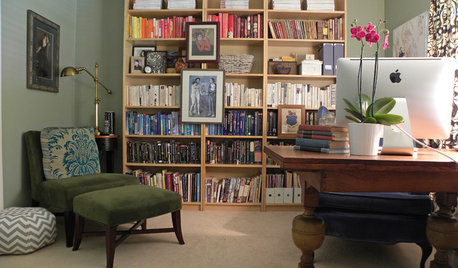

LIFESimple Pleasures: A Room of Your Own

Free up space for your own creative or meditative pursuits, and your dreams may have freer rein too

Full Story

FALL GARDENINGHouzz Call: Show Us Your Fall Color!

Post pictures of your fall landscape — plants, leaves, wildlife — in the Comments section. Your photo could appear in an upcoming article

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESShop Your Garden for Easy Holiday Decorations

Make your home merry and bright without all the stress and fuss — everything you need is in your own backyard

Full Story

WORLD OF DESIGNA Brief History of British Eccentricity

Britain is famous for its quirky characters. And some of the nation’s best interiors reflect this collective trait wonderfully

Full Story

HOLIDAYSCollecting Christmas Ornaments That Speak to the Heart

Crafted by hand, bought on vacation or even dug out of the discount bin, ornaments can make for a special holiday tradition

Full StorySponsored

Columbus Area's Luxury Design Build Firm | 17x Best of Houzz Winner!

More Discussions

tapla (mid-Michigan, USDA z5b-6a)

amccour

Related Professionals

Edmond Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Simi Valley Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Wareham Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Salem Landscape Contractors · Peabody Landscape Contractors · Eureka Landscape Contractors · Gresham Landscape Contractors · Melrose Landscape Contractors · Mount Sinai Landscape Contractors · Newnan Landscape Contractors · Rockwall Landscape Contractors · Vineyard Landscape Contractors · Waipahu Landscape Contractors · Gloucester City Interior Designers & Decorators · Queens Interior Designers & Decorators